Technical Morality with John Danaher

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Welcome to Pondering AI. I'm your host, Kimberly Nevala.

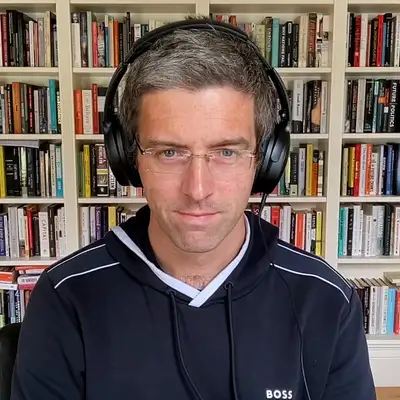

In this episode, we are so pleased to bring you John Danaher. John is a senior lecturer in ethics at the NUI Galway School of Law. He researches the ethical and moral implications of technology across a wide range of domains and is also the author of the 2019 book Automation and Utopia: Human Flourishing in a World without Work.

John joins us today to discuss how technology can perturb social mores, how we can mind the gap between current and future moral judgments, and the ethics of digital duplication.

Welcome to the show, John.

JOHN DANAHER: Thanks for inviting me, Kimberly. It's a great pleasure to be here.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: The pleasure is definitely all ours. Now, you have a particularly interesting background as a philosophical lawyer, I will say a little bit tongue in cheek. What was the bridge or the connection for you between your interest in the law and the philosophical and ethical impacts of tech?

JOHN DANAHER: I guess, as a child, I was always interested in science fiction and some of these more philosophical aspects of science fiction. Questions around what does it mean to be human versus a machine, the kind of relationships between humanity and technology, and then ethical and social issues as they're explored in science fiction worlds.

And as I grew older and I studied law and I went into research, I found a way to bridge that connection myself, that a lot of the more fanciful questions that I was interested in as a child were becoming perhaps more real-world questions and as a result of technological advances. So I just naturally segued into that topic as a result.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: That's a lovely circumstance if you can find it.

Now, I found your work originally through some collaboration you did with Henrik Skaug Sætra, who's also been here on the show with us. We're huge fans of him. And it was some analysis you were doing about the six ways that technology impacts or changes morality. This was very striking because there is a lot of conversation today, particularly in the responsible AI or the ethical AI domains, about how do we ensure AI, in particular, aligns or enforces, reinforces existing cultural, social norms, ethics, and so on and so forth.

And this really took a slightly different view of it in terms of asking the question differently. Which is, how might the technology, for better or for worse, disrupt or shock existing social mores. I don't know if it's by definition or by design, but just by virtue of us using it and putting it out in the world? For you, why was this an interesting or important way to approach the topic?

JOHN DANAHER: Well, I mean, there's probably, maybe a slightly cynical or instrumental reason for doing it, which is that, as an academic or researcher, you're always trying to find the spaces that people aren't exploring or to look at topics from a direction or perspective that other people aren't adopting, because that's a way of standing out from the crowd.

So as you pointed out in that paper and in several other papers, including ones that I've written with Henrik, I guess I was inverting the typical direction of analysis between ethics and technology. So at least in the communities that I interact with in academia, the typical direction of analysis is to use existing ethical norms and principles to evaluate technology. And to a large extent, that's what the entire field of AI ethics does and, before that, let's say something like medical ethics or bioethics. They were looking at developments in technology and using traditional ethical frameworks and principles to evaluate those technological developments.

And in that paper, we were coming at it from the opposite direction. Which was looking at how technology might actually reshape our ethical principles and frameworks. So it just seemed like an obvious thing to do, which is to just do something that's slightly different from what everyone else was doing.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: And in the paper that I referenced and the other related works, who is your primary audience or who are you speaking to typically?

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, I mean, with that particular paper, I guess there were two primary audiences that we were interested in. I'm not sure how successful we've been in reaching either of them.

But one would be academic philosophers and ethicists or people interested in maybe like the soft side of technology, if you like the social implications of technology and the people researching that topic. And then secondarily or complimentary to that, we would be interested in people who are actually designing and creating the technologies using the framework that we presented in that paper.

So as you already mentioned, there's six mechanisms through which we think technology can change social/moral beliefs and practices. And we think it would be useful if people who are actually designing technologies would have that framework in front of them and say, oh, we're creating this device. It could have the following effects, which could have the following impact on social morality and maybe stop for a minute and think about whether that's a good or bad thing, whether it's something that they want to double down on and encourage, or maybe we want to step back from and resist those kinds of changes.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: I thought this was really an intriguing but also a very practical angle or another angle into what are becoming fairly pervasive - or at least we are all campaigning for them to become pervasive - impact assessments for AI systems. Certainly as we start to look at things like the AI EU Ya-- AI EU Act-- absolutely designed to be a tongue twister for me. In any case, organizations will need to do this.

But all of these systems and frameworks today focus on identifying risks and harms and that can feel a bit esoteric. But it also prejudices, as I think you just alluded to, towards what is today.

So in looking at these factors, it not only didn't feel ethically squishy to me because if I can look at this and say something very definitively: how does this change somebody's options? How might this enable a new relationship? How might this change the duties within the context of an existing relationship? It is - again, it may be practical - it's a different way of asking those questions that feels more accessible in a lot of ways. And it is also, perhaps, stealthily asking folks to engage with ethics, morals without telling them to do so. They're implicitly engaging it without doing it explicitly. And (for) anyone getting into this area, it can feel very uncomfortable.

So are there specific elements or factors that you identified here that you think are most pressing or pertinent with regard to the current trajectory of AI today?

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, sure - maybe just to comment on one of the things you said. I mean, there's a significant difference between the framework that we've presented in this paper versus something like a traditional ethical framework or even a regulatory framework like the AI Act.

Which is obviously that those frameworks are what we might call negatively oriented insofar as it's like, well, here are the principles, and here are the ways in which you might be violating them and don't do this. So they're framed in terms of don't undermine someone's privacy in the following ways, don't cause the following kinds of harm or risk. Whereas our framework was a little bit more exploratory. Which is like, think about how the technology could impact this and how this could lead to these secondary consequences. So it's actually foregrounding the mechanisms through which people's behavior is changed and then, as a consequence of that, how this could affect moral beliefs and attitudes. So it's getting the person using the framework to do that work themselves rather than telling them what's right or wrong and so forth. So that might be an important difference between them.

But to go to the main question, which is what are the important ones? So very, very quickly. There's obviously six of them and they are framed at different levels. We divided it into three main branches. So we say that technology affects decisions and decisions have moral aspects to them. It affects relationships. Relationships are obviously sources of moral value and moral duty. And it also affects perceptions, how we think about the world in a morally coded or valenced way. And then within each of those three branches, there's different mechanisms at play.

Decisionally, technology changes option sets, we say. I mean, initially that was actually technology adds choices to life, which I think is probably the primary mechanism of change. That it makes things more complicated, it gives us more options. There are perhaps sometimes when technology can reduce options or make certain options less salient. And so that's why we said changes option sets as opposed to adds options. Technology also then changes the costs and benefits associated with choices. To be honest, I think of those two things, the decision ones, as being the primary and most important because they are ultimately the foundation of the subsequent mechanisms.

So in the relational domain, we get new relationship partners, that's a new option in a sense. It changes the benefits and burdens within relationships. It changes the balance of power within relationships. That's largely a function of how technology alters costs and benefits.

And then the last one, which is a bit more nebulous and maybe harder to predict is that it changes the kinds of information that we're presented with, which can be morally salient. And that can often be linked to costs and benefits as well, like what we think the perceived cost of an action is, and also maybe gives us new moral metaphors or mental frameworks for thinking about things. That one’s maybe a bit more abstract.

But I tend to think of the first two - how technology affects decisions by changing option sets or by changing costs and benefits - as being the most important overall.

I guess to link it to AI, there's a range of ways in which AI changes decisions. Take something like generative AI and in my own field of academia or education, it changes options. That, say, for students when they're trying to do a college assessment or assignment or any assessment or assignment. They can do that with the assistance of the technology, they can outsource maybe entirely their efforts to the technology.

That's an ethical choice that they make. Is that something that should be encouraged? Some people think it should be allowed; it should be permissible. Some people think it should be forbidden. So it raises this new moral dilemma for everybody. Should we avail of the technology in that way? And, obviously, it changes the costs and benefits of certain options as well.

It makes it a much cheaper and easier to produce lots of content, lots of material, lots of stuff. Maybe is less high-quality stuff or the quality is more dubious in certain ways. Maybe it's higher quality stuff for some people. But it definitely has this effect on the costs and benefits of certain choices and that can, in turn, have a variety of moral implications.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: And one aspect of this that really caught my attention initially was that second factor around relationships as we have a lot of discussions these days around are these tools, are they assistants, are they partners? There's a lot of language. And the use of that language, I think, in a lot of cases is deliberately used sometimes to obscure or to promote a point, but it can get very confusing. So this idea of thinking about AI and AI systems as colleagues, or as teachers, or as friends is one element. I think that's really interesting and it's hard for people to talk about.

So I think this approach of thinking about how might it change how you relate to each other, or to something else - to the tool itself - it's a profound question to ask. But this is an interesting on ramp that it feels less overwhelming to me and very objective. And something that almost anybody, regardless of their background - whether you're the developer, or an engineer, or an analyst, or a manager, or some at the board level - could talk about.

But it also opens up that conversation around how is this changing how we look at each other. And we're going to talk about digital duplicates in a minute, but there's a lot of hypering, I think we would still have to agree, around AI as being, becoming, these highly capable, independent actors capable of anything. They're going to be your friend, they'll be your teacher, they'll be your counselor. It's definitely not clear that that's even possible or true, nor is it clear that it would be desirable.

But, again, that element of just asking the question. Because even something like the duty of care, how does this change duties within a relationship? If we think that this is true, how does this change how we think about our duty to care for each other, to educate each other, to care for our elderly, so on and so forth?

So, again, interestingly, I take the point on the decision piece, although I think sometimes that's an area that's easier for folks to conceptualize. And what really caught my eye, not because it's more important or less important, was the relationship piece. Because it seems particularly relevant to a point in time we are, or how we're talking about these things, and how these systems are starting to manifest.

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, I mean, one potential reason for that - what resonates more is that - I mean, the decisional stuff is quite, maybe, abstract. And it's almost framed in that paper in terms of classic decision theory cost-benefit analysis or maybe even an economic mode of analysis there. So maybe it seems a bit more detached from the moral domain, even though I think it is connected to it. Whereas the relationship stuff or the relational dimension is more obviously moralized for people.

There's a reasonably famous philosophy book by T. M. Scanlon, or Tom Scanlon, who was a Harvard professor for years, called What We Owe Each Other which is based on this notion that the central aspect of morality is this question of what do we owe to one another? So the central moral question is a relational one about how we relate to our fellow members of our moral communities.

And so what you're talking about there in relation to AI is that it is potentially perturbs or disrupts our sense of who or what belongs in our moral community. And so if it's the case that AI assistants or chatbots occupy some uncertain status, we don't know: are they just are they tools, as you say? Are they colleagues? Are they potentially friends? They occupy this liminal status at the moment where we're not sure exactly how to categorize them morally speaking and that obviously has significant moral implications.

Because if they're just a tool, then we don't have to think about our relationships with them in moralized terms. If they are a colleague, maybe we have to start thinking about it in those terms. If they're a friend, it seems like we certainly have to think about it in that morally loaded way. Obviously, there's also perhaps, corporate agendas or individual people's agendas that would benefit from creating uncertainty about their status or categorization as well that we need to be conscious of.

But, also, irrespective of that, within relationships, the fact that we use AI perhaps to assist with our own relationships with others effects the moral domain as well. Again, if you're a student, do you have to achieve some kind of duty of transparency or openness to say that, oh, yes, I did use an AI assistant to help me draft this essay or draft this report. Does that apply if you're an employer? Employee? Does it apply if you're somebody like me, a researcher?

A lot of journals now, when you submit papers to them, they say, we don't accept AI as an author. So you have to issue these declarations about whether you've made any use of them and to what extent you made use of them. Some people say not to make use of them at all. Clearly, lots of researchers are not being honest about that because there's lots of papers out there that have text within them that was clearly generated by GPT or something like that. You can, if you're interested, search on Google Scholar or something for phrases like "As of my 2021 update, I don't have this information.” You'll find lots of papers out there that have been published with that within them.

So, yeah, that's just one example that, if you're using AI in some way to create output for yourself or assist you with something, do you have a duty of transparency with respect to how you use it? And it seems like different people in different contexts aren't fully sure about that. I guess the irony, again thinking about my own terms as a professor, many professors would say that their students have a duty of transparency, but they're actually not sure if they themselves have a duty of transparency when it comes to their own work.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Yeah, interesting. That's interesting. Yeah, and I think the second order effects, again, this is an approach or a way of asking these questions - and I've been through a lot, I've spoken to a lot of folks with the frameworks that we have today for assessment and for moral and ethics alignment and all of these components – to get us to think about and talk about in a fairly nonjudgmental way even second order effects.

So regardless of whether you think an AI system can be your friend or a colleague - or is just your now go to source for information -it may change not only how you interact with that system, that is one thing, but your expectations for other people - for real people in the real world. I use the term "real" cautiously because I think that's a bit fraught in and of itself. But your expectations for how other folks relate to you, the level of grace we provide to other people for their fallibilities, our tolerance, accountability for each other. We talk a lot about this in the responsible, ethical AI space and this is a very accessible and understandable way to think about it in a way that's not very threatening. So, yeah, all of that is interesting.

Now, you had some separate work, I think, that's related - in my mind, I connected it although it may or may not have been- talking about the anticipatory gap. Because one of the other elements that this work starts to push on is the fact that we shouldn't expect that the social and cultural norms, mores are going to be the same in the future. Not only will the technology, by virtue of how we use it and deploy it, maybe change those components, but there's a lot of other factors that may as well.

So this idea of the anticipatory gap-- you wrote about it or at least where I found it was talking about heritable genome editing - you were part of a set of authors on that paper in which you talked about needing to use anticipatory governance to ensure that moral uncertainty doesn't create governance paralysis.

And it seems, again, particularly timely relative to the AI space. Where our inability to really project how and where these things may or may not be used and what their long term implications are is very fraught. A lot of people have a lot of ideas and some of those ideas are just diametrically opposed.

So when you think about .. first of all, can you explain to folks what the anticipatory gap is? And then I'd like to talk a little bit about how organizations might think about anticipatory governance in the context of AI.

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, sure. So probably the most famous statement of the anticipation gap, or the person with whom it's most associated with is a guy called David Collingridge, who is a sociologist and philosopher of technology at, I don't want to disparage him, but a somewhat obscure UK university in the early 1980s called the University of Aston. And it mightn't even have been a university back in the early 1980s. It became a university subsequently.

And he wrote a book but within the book he had this idea of something called the control dilemma, which is subsequently become known as the Collingridge dilemma in honor of him. Which is basically that there's a dilemma or trade-off when it comes to any emerging technology, which is that when we know relatively little about it and about its impact on the world, we have a lot of control over it. But when we know a lot about its impact on the world, we have less control over it.

So you can think about this in terms of timelines. Relatively early on in the development of technology, it's easy to control it, and constrain it, or develop it in certain ways. If you want. But you don't know the effect that will have on its social outcomes. But later on, it's difficult to control and change the direction of travel.

I tend to think about the smartphone as being the quintessential example of this and that when it was created back in the early 2000s or it became a mainstream device, let’s say, through the iPhone in particular, we didn't really have as clear a sense of the impact it would have on society. And now in 2024, when we're recording this, people are having a lot of concerns about its social impact, and rethinking our relationship with it, and trying to regulate and control it at a point in time when it's much harder.

One obvious manifestation of this problem, let's say, comes in relation to children and their use of smartphones, particularly in schools. I don't know what it's like where you're living at the moment, but in Ireland where I live and also in the UK, recently there's been an attempt to seriously clamp down on student use of smartphones in schools in particular. Some elite schools in the UK, for example, have taken to banning phones amongst their students. And recently, anyway, the Irish minister for education has suggested that they're going to ban phones for students in schools.

But it's very hard to do that now when the devices become so ubiquitous and when parents have become very reliant on them. Parents themselves are probably addicted - maybe a strong word - but heavily dependent on the technology themselves. It's perhaps hypocritical or challenging for them to control their children's behavior in relation to it.

But it would have been relatively easy to do this back in 2007 when the device was created; to create guidelines and strictures, but we didn't know the impact it would have. Now, once we know the impact, it's very hard to put those guidelines and strictures in place, even though we might end up doing it.

The anticipatory gap, I guess, is this notion that when it comes to governing something, it's easy at one point in time, but we can't anticipate the effect it's going to have on society. It becomes harder once we know more about its effect.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: And it certainly runs - I don't know if it runs counter, but the prevailing-- at least from companies and the big tech companies today and actually not just the big tech companies-- folks who are worried about stymieing innovation or slowing things down prematurely are arguing somewhat the opposite. Which is to say, we don't know how it might be used and what the impacts will be, therefore, we should not regulate it in any way, shape, or form or with a very light touch today until we know what those pieces are. But this hypothesis would suggest that it's a good way of avoiding regulation and constraint today but it is not setting us up necessarily for success in the future either.

JOHN DANAHER: Well, I mean, it's very hard to know.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: It's a conundrum.

JOHN DANAHER: I mean, I emphasize one aspect of smartphones as well, which they also clearly have benefits, have beneficial aspects. And so if you don't have some freedom or scope for people to innovate with the technology or explore potential use cases, you don't get the upside either. So that's why it's a dilemma. It's a trade-off.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Right.

JOHN DANAHER: You got to decide where do you want to fall in it. Do you want to try and slowly control the release of something or do you want to just let the market decide or let people decide how it's going to develop and what the best uses are of it.

The use of smartphones amongst let's say, young adults in particular, but probably everyone really, or young people in particular, illustrates the potential costs of the technology. I mean, it seems obvious to me, both individually and as a parent, that there are a lot of concerns about the use of this technology amongst younger people. I know people disagree with that, of course, and we will say the research isn't as clear cut. But I would certainly like to delay my children having a smartphone for as long as possible. And I know most other parents think roughly the same-- at least the parents that I interact with.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Yeah, there's been some interesting studies and it’s very early days here as well. But some school districts here, particularly on the West Coast in California, are doing things like putting lock bags for phones. And then they're talking about - and, in my mind, I'm thinking just even the physical aspects of this - kids are figuring out how to bring magnets in, and unlock them, and get their hands on them. And yet they're saying when we take them away, we see a whole different level of engagement and socialization and not just attention in classrooms. But, on the other hand, especially for older kiddos, they're used to having that in their hand and they feel bereft without it.

So when we think about then that anticipatory gap as companies or societally, one of the elements that did jump out there was the need for public engagement in these conversations. It's not obvious to me that we have good mechanisms for supporting that, even within organizations, much less broadly today. Would you agree with that or have you seen elements of public engagement or other aspects, other processes, protocols that people bring to bear to have the conversation around this anticipatory gap and decide how to address it?

JOHN DANAHER: I mean, it probably depends on where you are located in the world.

I think the European Union can be criticized perhaps for the way in which it constrains or limits innovation with certain technology, but, I think, it, generally speaking, does a better job with its regulatory frameworks of managing what they would call responsible innovation. Which involves a greater interaction between the private sector and the public sector in how technology is rolled out, sometimes through large regulatory agencies, which are supposed to interact with stakeholder groups and who are affected by technologies. You can see this in relation to data protection in various European Union jurisdictions.

I presume this is what's going to happen with AI in the EU. It's very early days. We only just really have the law in place now, so the infrastructure around the law needs to be set up and tested. And the history with data protection isn't exactly a positive either or it's not obviously positive. But there is that greater emphasis on this regulatory model of responsible innovation, which constrains and slows down the use of technology to an extent but has raised feedback mechanisms for populations of people who are affected - civil society, organizations, human rights organizations, et cetera - feeding back into the way in which the technology is regulated and managed. I can't really speak to what it's like in the US, but my sense is that it's different.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Yeah, we're working on it, but it's a little bit more of the Wild West here still for a number of reasons. But…

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, and just to be clear, there are people in the EU who'd be very critical of the EU's approach as well on the grounds that it means that the EU is not driving the change in this technology or driving innovation of this technology. That it's really the US and, maybe, China to some extent that are driving innovation in this sphere. And the EU is primarily a user of that technology as opposed to an innovator in the technology.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: So I wanted to round out the conversation today talking about some of your work in the area of digital duplicates. Again, with the recent absolute and public availability and explosion of generative AI, as well as the continued improvement in other forms of artificial intelligence, this is now a very timely and top of mind topic for everybody. We will link to some of the papers that you've had here. But how do you define a digital duplicate for purposes of this conversation?

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, sure. So a digital duplicate for our purposes is at least a semi-autonomous and partial recreation of a real person in a digital form.

The most obvious digital form nowadays is going to be like an AI chatbot. Probably running off GPT or some equivalent technology, where you have the basic model, the foundational model, but then it's fine-tuned on data from a particular individual. And so it can generate responses in the style of that individual. I mean, that's one illustration of it. Another illustration actually that we use in the paper - a little bit more elaborate - is there's a Japanese roboticist, whose name I'm now going to blank on. Hiroshi Ishiguro, I think is his name, and for years he's been going around with this robotic dummy of himself. But for the time being, for most people, the AI chatbot version of a real person is going to be the most likely manifestation of this technology.

I first became interested in this in the wake of hype around GPT when you had people doing certain stunts with it. So, I mean, two stunts that stand out are there's a German magazine that got into trouble for conducting this interview with Michael Schumacher. So Michael Schumacher has been in a, I don't know what the politically correct term to use is nowadays, but some kind of locked in state, basically, that he can't speak and talk to people due to brain damage as a result of a skiing accident years ago. As far as we know, he can't speak or interact with people as he used to. But this magazine conducted an interview with him based on this bot that had been trained on some of his previous outputs, a bit of a stunt or publicity stunt, which backfired for that magazine.

A more interesting example was the philosopher Daniel Dennett is a well-known philosopher of mind and evolutionary theory who actually died earlier this year.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Passed away recently.

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah. While he was still alive, he consented to a German researcher, Anna Strasser, creating a GPT-based version of him. It was based on an earlier version of GPT, not the more recent models. But it was trained on his writings and Strasser, along with a couple of other philosophers - the Schwitzgebel brothers, I think - did this test, basically, where they got experts in Dennett's philosophy to evaluate responses given by this AI chatbot version of him. And they struggled a bit to differentiate between the real version of Daniel Dennett and this AI version of him.

And Daniel Dennett subsequently wrote a few pieces before he died about his unease actually about this technology, even though he consented to this originally. It seems like he wasn't entirely convinced of the merits of doing this kind of thing afterwards. There's an interesting footnote, actually, he wrote in his memoir, which came out in 2023, where he expresses some concern about the technology.

So this is interesting to me because you can actually really do this for almost anyone now as long as you have a sufficient data set, and lots more people are doing it. There's another philosopher, Luciano Floridi, who consented to having an AI chatbot version of himself created that not only would issue responses to questions in his style but would innovate in its answers. You could ask this AI version of him anything, his opinions on politics or something like that, and it would generate a response.

I'm concerned about this from an academic level because there's cases in during the pandemic where universities recorded lecture material of staff, who subsequently died, and continued to use it for students. And so I'm wondering, what if my university decides that they don't need me anymore and they just want to create a digital version of me? I probably have enough data out there for them to construct an AI chatbot that's reasonably good as a version of me. Maybe that would be better than me in some ways; be more available, more responsive, perhaps, to emails or queries from students.

So now that we have this technology and we're able to create these digital duplicates, as we call them, of people, how should we think about that ethically speaking? Is that something that could be encouraged in certain contexts or it should be discouraged as much as possible? Where should we stand on that issue?

KIMBERLY NEVALA: And to address that issue - and, by the way, no, I don't think you can be botified and get the full John Danaher experience, although it may appear that way for a minute. You have developed, in concert with some collaborators or collaborator, this idea of the MVPP. Not the minimally viable product, but a Minimum Viability Permissibility Principle. Can you talk to us a little bit about that?

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, it's a bit of a mouthful. But we're just borrowing a term from tech entrepreneur circles about the minimally viable product for the minimally viable permissibility principle. Which is, you could also translate it as the maximally agreeable principle. What's the thing that most people are likely to agree to.

So there's lots of potential harms and also potential benefits associated with this technology. How do you get the right ratio of the two things. So we proposed this principle with five conditions in it that need to be satisfied before the use of the technology is permissible. I'm going to just read it out.

So what we say is that in any context in which there is informed consent to the creation and ongoing use of a digital duplicate, at least some minimal positive value realized by its creation and use, transparency in interactions between the duplicate and third parties, appropriate harm or risk mitigation, and there is no reason to think that this is a context in which real, authentic presence is required, then the creation and use of the digital duplicate is permissible.

So a bit of a mouthful, but you've got five conditions in there: consent, transparency, minimal positive value, risk mitigation, and the authentic presence condition which is that in some contexts you want to be interacting with the real person, not a digital duplicate of them. And if it's a context like that shouldn't create and use the duplicate.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: And at the risk of going to the most pedantic, because there's really interesting elements, I think, to consider in each of those. We could spend an hour probably on each, but also just walking through just this element. This idea of informed consent jumped off the page at me from the start because it is not at all clear today, given the level of broad public literacy and understanding of what these tools really can do, what their actual limitations are, how they, in fact, work. I think those of us in the field overestimate how much folks outside the field really do understand and think about mediating their use of these technologies or what they might agree or not agree to.

There's an inevitability narrative out there, too, which says it's going to happen so I might as well jump in whether I agree to it, support it, or engage with it. Without a real sense of what its real and present and future usage and what the implications in the future might be as well.

So I have to assume then part of assessing the MVPP is it's not just a one-time check the box and move on. It is something that has to be assessed and reviewed on a continuous basis as well.

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, I mean, just to pick up on consent.

Informed consent conditions are common in many areas of law and there are problems with them in other areas of law too, like medical informed consent. Do people really know what they're consenting to when they consent to certain operations? Even if you quantify the risk for them involved, how accurate are those quantifications and how do ordinary people really understand the difference between a 5% risk of something versus a 10% risk of something or a 1% risk of something. It's not - there's all sorts of weird biases and problems in the way in which people think about those risks.

But, yeah, I think one of the main problems with the consent condition is that there are probably weak consent norms in the technology sphere anyway. People maybe do have this learned helplessness or fatalism around the technology that they'll just consent to anything without really thinking about the harms of it. The benefits of the technology are often immediate and obvious, whereas the potential harms are fuzzier and longer term. That's a concern that a lot of people have around consent in the world of data protection, for example. And that's actually one reason why consent is not the only condition required under the EU data protection law, other conditions have to be satisfied as well.

But, yeah, also consent would have to be an ongoing thing. That's a common idea that it's not just a one and done thing. You have to consent to the ongoing use of the duplicate. And if there's any change in its use or change in its functionality, you would need to be informed of that and consent to that as well. Very hard to implement this in practice, of course, given the availability of the technology and the ease of use. But that's what we think ought to be done in this context.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Yeah, hard questions asked, but questions that need to be asked. I mean, even just things as basic as establishing what's positive value, something that you talk about in that paper as well. Which, again, is it to the duplicator or the duplicated, who may or may not be, that may not be the same, one in the same. Or then is it the value to those who are engaging with it in their perspective? So even that which should seem fairly straightforward…

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, I mean, if there's one thing I could say just about this as well, which we emphasize in the paper - what I think is maybe the important takeaway from the paper-- is that we think that actually satisfying the fourth condition-- this risk mitigation condition-- is incredibly challenging because it's very hard to constrain or control the use of duplicates.

The analogy we would draw on the paper is like when they digitize musical files. You might have copyright protection and property protections over the music files, but, of course, anyone can create and copy them. It's just so easy to do it. So it's harder to police those rights.

The same problem is going to arise in relation to digital duplicates. Once they're created, it's just going to be so easy to copy them and port them over to some other context. It's very hard to control the uses of it and that's going to expose you, if a digital duplicate of you is created, to a lot of potential harm that you didn't really consent to or you weren't informed of.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: So bottom line, if your university asks to create a digital duplicate, is your answer still no?

JOHN DANAHER: I, yeah, I don't think anyone should consent to it. I think the problem is that people can do it and not tell you or inform you about it.

And, I mean - sorry, another thing that I do comment on in the paper briefly is that actually in many countries, existing intellectual property protection laws entitle employers to the IP of their employees. If you're a programmer and you have the original ideas about programming or something like that, your employer is usually entitled to your ideas. Does that mean that they're entitled to create an AI version of you if that is the medium for the ideas? It's a tricky question. Probably not, I would hope, given that you're not just copying the ideas themselves, but it could give rise to difficult legal questions in practice, given that existing framework.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: So we've got just a few minutes left here. What are you finding most interesting right now? That can be things that you're focusing on moving forward, or maybe questions that folks are asking you, or that this work is raising that is most engaging you at the moment, or, frankly, just any final words for the audience?

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, I mean, I think the stuff around digital duplicates is quite interesting. It's gone from essentially being something that wasn't on people's radar, let's say, two years ago to something that's now possible and, I think, worthy of greater scrutiny and analysis. And people are starting to provide that at this stage. But that was something that excited me or that I thought was important to get involved in the debate or discussion around that early on.

My main interest, academically speaking, remain more on the first topic that we spoke about today. Which is the impact that technology has on our moral beliefs and practices, how it can shape and rechange them in various ways. I'm very interested in the history of this, looking at it in a very long historical perspective from the dawn of agriculture up until the modern information communication technology age. So I'm doing a lot of work on the history of technology and moral change with a view towards better understanding the future. So that's the thing that occupies my time most at the moment.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: That's awesome. I really appreciate all your time today and the insights you did share. We took what I think can be best categorized as a quick tour through a lot of your work here today. And I would encourage folks to spend a bit more time with all of it.

And as you mentioned the work up front, I'm really interested in how we might use this framework and this approach to thinking about the impacts from an ethical and moral perspective to engage more folks, even at the ground level in organizations, in this conversation. It is a different, as I said, a different entry point and for whatever reason feels like something people would be able to consume and engage with in a really natural way. So whatever we can do to help do that… So thanks again. I really appreciate your time and the insights today.

JOHN DANAHER: Yeah, and thanks for making the time to talk with me, and read up on my work, and be able to ask questions about it. That's always gratifying-- better than being ignored anyway.

KIMBERLY NEVALA: Well, we'll have you on again and maybe we can do some deep dives.

Thank you, everyone, as well for joining us. If you would like to continue learning from leading thinkers and advocates, such as John, please subscribe to Pondering AI now. You'll find us on all your favorite podcast platforms and currently on YouTube.